I have spent the

better part of the past year working a route named Trench Warfare in Logan

Canyon. This is the sport Trench Warfare, not to be confused with the trad

route that bears the same name in Little Cottonwood Canyon. Both happen to be

crazy horizontal offwidths, but the Trench I fell in love with is located in

the iconic…at least it used to be iconic…China Cave, home to Super Tweak, the first 14.b put up by an American in the US. The crag was bolted by

Boone Speed, Geoff Weigand, Bill Boyle, and Jeff Pederson…the Dream Team of

90’s sport route development (and luckily they didn’t stop then). Of course

this means exactly what it sounds like, that not all of the holds are

“natural”, and partly because of this, the crag seems to have fallen out of

favor with the climbing ethics police over the past ten years or so. The routes

are heavily manufactured, with fantastic movement built in. From what I can

tell, my Trench Warfare is exactly the opposite of the other Trench Warfare.

I first saw Trench

when I flew to Utah from Michigan to visit Charlie in September of 2009. I had

done several easy 5.12’s in the Red River Gorge, which was my

six-hours-from-home crag, and was excited to try to climb 5.12 somewhere new. I

spent my day at China Wall fruitlessly working the classic China Cave entry route,

the Oboe. At that time, the Oboe had a winch start (which seemed weird to me,

given the “artistic” nature of the crag), which many of the routes shared and

then traversed to different exits. A couple years ago, pockets were added to

the Oboe start, so now the entire line is climbable, with moves that don’t affect

the grades. There’s nothing to stop protestors from winching to the first bolt

as in days of yore if they really, really wanted to.

Trench Warfare takes

the prominent line through the middle of the cave. New visitors to the crag

descend the short slope from the trail, and invariably halt under the wide

split in the rock and look up. You can watch their gaze move from the initial

slabby blob that gets you off the ground, to the powerful opening moves into

the roof, and then travel up the chasm to where the angle changes from

horizontal to first 45, then 30 degrees, finally topping out in a powerful, techy, slightly weird

dihedral. Grade consensus on the first 25 or so feet of the route is 13b, into

20-25 feet of 12c, with the weird finish being the crux of a 12d. The route is powerful,

and I am not, but when I saw it all I could think was that I was going to do it

someday…someday.

|

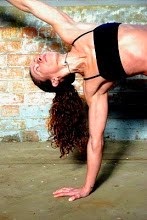

| Kneebar #1. Photo: Taylor Roy |

|

| The "big move". Photo: Taylor Roy |

Getting on Trench took some manipulation of circumstances. Charlie had already done everything he felt he could at the crag. We were in mid-season power retrieval mode, climbing what basically amount to bolted boulder problems at another Logan crag, Quality Cave. Two weekend days in a row on the short power problems were killing us, so we agreed to go back to China Cave on Sundays. Charlie’s plan was to run laps on routes he’d already done just to keep up his fitness and endurance. Mine was to determine if I thought I would ever be able to climb Trench Warfare.

It took me several Sundays

of work just to unlock beta for the boulder problem off the slab. After that,

there’s a short rest before starting into my personal crux, which starts one

move before what’s widely considered to be the actual crux. In exchange, a

short girl knee scum gives me a little extra something on the exit move. The redpoint

crux is a powerful cross-through from a left-hand two-finger pocket to a crimp hidden

in a sea of slopey-ness for the right.

As of right this

minute, I’ve managed to pull off an ascent of a variation of the route that (for

me, at least) ends on a slightly easier finish. I’ve fallen on the last hard

move of Trench Warfare proper. All I can do is keep trying. If I give up now,

I’ll never know where this particular journey ends. Just like trading my grown-up job to work in the climbing and yoga worlds. Just like moving to Utah to live with a guy I'd been dating long distance for six months. Moving forward, never stagnating, and learning as I go...after all, isn’t that

really is what this game of redpointing is all about?